If there was one thing that truly captivated the kids during this journey, it was the animals. From the dogs and donkeys in Jordan, to the sea turtles and camels in Oman, the elephants in Sri Lanka, and the bears and bison in America, they’ve been fascinated at every turn. So, they’d been eagerly awaiting their first safari in Namibia for a long time, and their patience was finally rewarded.

The Big

We had been sitting in our guide’s 4×4 for an hour and a half, watching the spectacle of five lionesses devouring a wildebeest. They were sprawled out side by side, three on one side, two on the other. Every now and then, one would growl and get agitated, defending her piece of meat when another tried to take a share of the meal. A hyena and two jackals waited their turn, and two more lionesses were patrolling nearby. Anna was the most attentive, completely mesmerized by the scene.

Despite the early morning chill in Etosha, in northern Namibia, we had risen before dawn, met our guide Ismaël, and set off in search of wildlife. “No promises. These are wild animals, but I’ll do my best, and if we’re lucky, we’ll see some of the Big Five,” he told us. And lucky we were.

These are the animals everyone hopes to see on safari. While Etosha doesn’t have buffalo, it’s home to plenty of elephants, both black and white rhinos, leopards, and, of course, lions, with an estimated population of around 2,000. But with a 20,000 km² reserve—about half the size of the Netherlands—these animals can still be difficult to spot. Only the southern part of the park is accessible to visitors, while the rest is a vast stretch of untouched wilderness, a paradise for wildlife, and one of the largest nature reserves in the world.

After two days of driving through the park in our 4×4, we saw (many) elephants, (a few) rhinos, (plenty of) giraffes, and (countless) zebras and antelopes, from springboks to kudus and oryx. On the second day, we were lucky enough to encounter two lions on the move. A male and a female strolled leisurely through the tall grass. Later that afternoon, as we stopped near a large watering hole, Anna gave us a little lesson on the wild world of Freek (a children’s show about wildlife).

It was 2 p.m., the sun was hot, and several groups of elephants had gathered to cool off by the pond. One group of about 15 elephants, including a male and two young ones, was already drinking when another male approached from the plain. We braced ourselves for a possible confrontation between the two males, but Anna confidently said, “They’re not going to fight. Look, that elephant is putting his trunk over his tusks—it means they’re friends.” I looked at Anna, surprised, then turned back to the elephants. Sure enough, the two males exchanged a few gentle taps with their trunks, then went back to what they were doing. Proudly, Anna looked at us and said, “See, I told you so.”

To increase our chances of seeing the rest of the Big Five, we decided to do a game drive on our last day and head out on safari with a professional guide. They know the park better than anyone and communicate with each other if one spots something interesting. It was the right decision. Without it, we would have missed this rare and unique sight. A “kill,” as the guides call it, is a real bonus considering lions are only active for about four hours a day and don’t eat every day. Our lionesses had taken down a wildebeest.

“The wildebeest is part of the Ugly Five, like the hyena,” Ismaël explained. “In Africa, they say it was the last animal created by God, who used leftover parts from other animals to make it.” Our lionesses were feasting, and, in a way, so were we.

Camping in Etosha is a unique experience. The park is closed at night and surrounded by electrified fences to keep wild animals out, but each campsite has a watering hole where wildlife comes to drink. Strange noises and wild roars echo through the night as you stay warm under your blanket. At dawn or dusk, all the campers and residents gather silently to watch nature’s spectacle unfold. What a show!

On the first evening, we watched in silhouette against the intense orange of the southern sky, as around twenty elephants came to bathe. They arrived across the savanna, holding each other’s tails. The kids were in awe. Then, giraffes appeared in the distance, waiting their turn, only approaching once the elephants had left. Usually so graceful and elegant, they became awkward and vulnerable by the water’s edge, spreading their front legs wide to drink, each one taking their turn.

On the second evening, we admired four rhinos in the night. These creatures are mesmerizing. Their strength is offset by their calm and tranquility. Everything about them is slow and deliberate. Their ears are constantly alert, listening for any noise. At every sound, they stop, look around, and wait for silence before drinking, bathing, or grazing. Two rhinos decided to extend their swim late into the night, and we went back to watch them after the kids had gone to bed. They were still young, occasionally nudging each other with their horns or making low grumbles. We couldn’t tell if it was a show of affection or strength, but we were captivated.

Then, suddenly, one of them turned and started walking straight toward me. Spellbound and aware of my luck, I didn’t move, trusting he wouldn’t go beyond the small wall and the electrified fence. I was fully aware that if he wanted to, he could easily cross both, but I stayed still. He stopped less than two meters away, his horn brushing the fence. He sniffed the air, looked at me, and we all stood there, motionless, watching. It was an incredible moment. He seemed to be saying that he knew we were observing him, and he was the one in control.

Of course, there were always a couple of people who would come up next to us and try to take a selfie with the rhino. Humans—they just don’t get it.

The Small

Namibia’s nature is beautiful, diverse, and varied, much like its landscapes. A few days earlier, we had experienced a different kind of safari—one in the Swakopmund desert, a coastal desert by the sea. No Big Five here, but instead, the Small Five. Guided by an expert, we ventured into the desert in search of the tiny creatures that inhabit it.

We uncovered a translucent gecko from its hiding spot—one that only comes out at night, blinking at us with its large, surprised eyes. Then, a silvery, legless lizard that lives beneath the sand dunes, and finally, a few venomous snakes that we disturbed from their resting spots. Often hiding at the top of the dunes, these little creatures wait for passing beetles and spiders looking for a bit of moisture. After that, the kids—and we—will certainly check carefully before sitting on top of the dunes, like we did at Sossusvlei, to make sure we’re not disturbing anyone.

We also learned about the extreme fragility of this environment, and how footprints and tire tracks can remain visible for almost 100 years, slowly degrading the desert and its ecosystem.

Our guide, Angus, spoke passionately about the desert and the life it harbors. He urged us to walk in others’ tracks and follow already existing paths. Occasionally, he’d place a lizard, gecko, or beetle gently into our hands, explaining their behaviors. He talked to us about the sand, the dunes, their colors, and how plants and insects harvest moisture. Each has developed astonishing strategies to survive in this harsh environment. These tiny creatures taught us so much about the desert, and the kids were even happier when we drove back across the dunes, with Angus thrilling them by speeding up to avoid getting stuck in the soft sand.

The Ugly

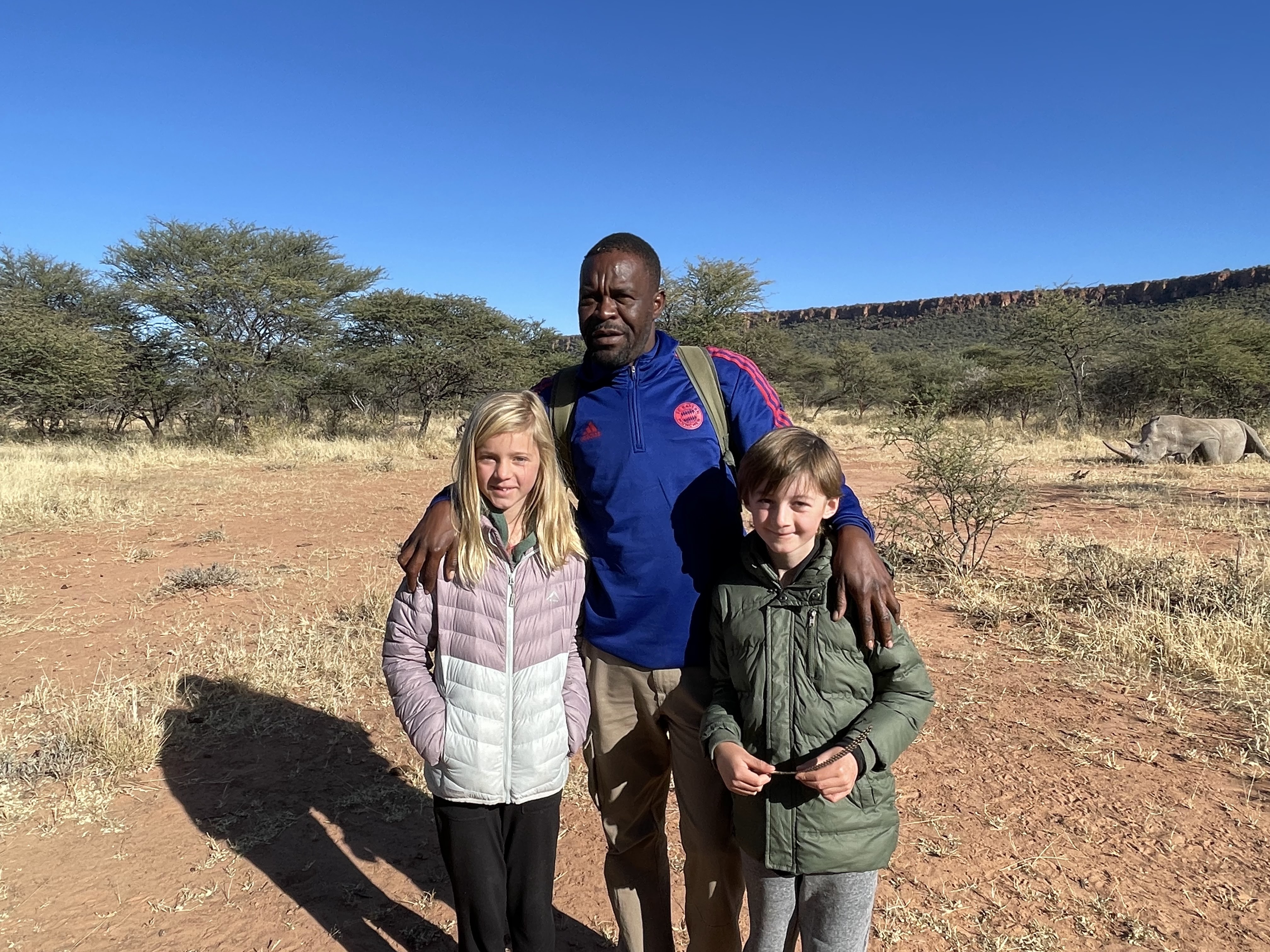

Our next stop after Etosha was the Waterberg Plateau. Etosha had exceeded all our expectations; we never imagined we’d see so many animals up close. For me, the most powerful moment was my face-to-face encounter with the rhinoceros. Of all the animals, the rhino is the one that moves me the most. So, when we had the opportunity to track rhinos on foot at Waterberg, we decided to brave the biting early morning cold (-4 degrees on the thermometer) and set out with our guide, Wesley, for a walk across the savanna.

Along the way, we encountered a few giraffes, impalas, warthogs, and dik-diks (adorable little antelopes, barely bigger than a dog). Then Wesley ventured deeper into the bush; he had found rhino tracks. We followed them, and there they were: dad, mom, and two baby rhinos resting.

The male was lying down, sleeping peacefully, while the others grazed nearby. Their ears were alert to our presence, and we were struck by their immense size. “Stay in a group, and everything will be fine,” Wesley reassured us. But I couldn’t help feeling uneasy being so close to such imposing creatures. One by one, the rhinos lay down and began to sleep. They had been active during the night, and now it was time to rest. They barely noticed us. Wesley explained the characteristics of the rhinos. These were white rhinos, and they only eat grass. The black rhino, which feeds on leaves, is larger. Their horns and temperaments also differ: the white rhino has a thicker horn and a calmer nature than the black rhino.

But what gives them strength has also led to their decline. Rhinos are critically endangered, partly because they are easy to approach and kill. Wesley grew visibly upset as he explained that 11 rhinos had been poached in Etosha just three days ago. We had been there. “How is it possible to kill such a beautiful and gentle animal? An animal that is our pride, that creates jobs by bringing tourists from around the world… How can we be so foolish? Most of our children have never even seen these animals, and if this continues, they probably never will!” Wesley’s frustration was palpable, and his words deeply affected us, though I wished he had chosen to express them a bit further from the four enormous, peacefully sleeping rhinos just in front of us.

Pour protéger ces animaux, certaines réserves cachent leur nombre et disposent de gardes armés. Mais la corruption et une pauvreté endémique permettent aux braconniers de bénéficier de la complicité de certains rangers, gardes ou policiers. Seule l’éducation peut permettre une prise de conscience de l’importance de la protection des animaux sauvages nous explique Wesley. “Pourquoi est-ce qu’ils tuent les rhinocéros ?” demande Arthur. Pour leur corne. Ils les envoient en Chine et au Vietnam où ils pensent que cela guérit le cancer ou d’autres maladies. Et c’est vrai ? C’est alors que l’un des guides nous explique que la situation est encore pire maintenant que l’Organisation Chinoise de la Santé a remis ce remède traditionnel sur la liste des produits autorisés. Jurgen et moi nous regardons ahuris. Comment est-ce possible ? C’est affreux.

Rhinocéros, girafes, éléphants, gnous, hyènes, lions, léopards, antilopes, phacochères, zèbres, serpents, gecko, lézards, scarabées et ces oiseaux colorés font partie de ces paysages vierges que nous avons traversés pendant trois semaines et demi. Qu’ils soient petits, grands ou moches, comme certains le disent, ils sont fascinants et rendent ces paysages encore plus majestueux. Finalement, la vraie laideur n’est créée que par les hommes.

Les enfants aiment les animaux et quelle chance ont eu nos deux juniors rangers de voir ces magnifiques animaux dans la nature, là où ils sont les plus beaux.